The Cellist Commanding Malaysia's Symphony, and Still Practising Like It's Day One

Orchestra & The Arts

•

November 22, 2025

The Cellist Commanding Malaysia's Symphony, and Still Practising Like It's Day One

Orchestra & The Arts

•

November 22, 2025

Share

Copy link

Share

Copy link

From the laidback streets of Ipoh to the concert halls of Scotland hall, Nasran Nawi's journey with the cello has been anything but ordinary. Trained in one of Europe's most rigorous conservatories, he returned to Malaysia not just as a virtuoso, but as a pioneer. Among the founding members who established the National Symphony Orchestra, Nasran helped build the institution that would define classical music in Malaysia for generations. Today, he stands on the other side of the music stand, baton in hand, leading the very orchestra he helped create. But ask him about his practice routine, and you'll find a man who still approaches his craft with the discipline of a first-year student. This is a conversation about legacy, humility, and why true mastery never stops learning.

A conversation with Nasran Nawi, Music Director, Malaysia National Symphony Orchestra

Words by Adinazeti Adnan

Photos : National Symphony Orchestra

The First Encounter

The first time I saw Nasran Nawi, I was nineteen years old.

An intern violinist with the National Symphony Orchestra, barely holding my own among seasoned professionals, I was overwhelmed by everything — the grandeur of Istana Budaya, the precision demanded in every rehearsal, the unspoken hierarchy that exists in any orchestra. And then this man approached me.

Not with the stern authority I'd come to expect from principals, but with warmth. Nasran Nawi was the Principal Cellist then, in the year 2000, and he simply wanted to know my name. To break the ice. To see how I was settling in.

I remember thinking he had the presence of a father figure — the kind of musician who saw young students not as burdens to tolerate, but as futures to nurture.

Then he looked at my violin.

Within seconds, his expression changed. Urgency replaced ease. "Wait — your strings," he said, reaching for my instrument before I could process what was wrong. I'd strung my violin incorrectly. The D and A strings were reversed, a beginner's mistake that could have gotten me scolded during rehearsal, especially under Datuk Mustafa Fuzer Nawi's baton, our conductor at the time. Mustafa was known for his exacting standards, his low tolerance for carelessness.

But Nasran didn't scold. He fixed it.

In less than two minutes, he restrung my violin, tuned it with practiced speed, and handed it back. "Cepat, cepat tukar. Nanti kena marah." Hurry, change it now before you get reprimanded.

He saved me that day. Not just from embarrassment, but from the kind of mistake that marks you early in a professional setting. I've never forgotten that moment — or the kindness behind it.

Nasran Nawi conducting National Symphony Orchestra at Petronas Philharmonic Hall

The Sound That Stayed

There was another memory, quieter but just as profound.

It happened during an opera production — Puccini's Tosca, performed by Istana Budaya sometime around 2001 or 2002. The NSO was in the pit, accompanying the singers, and there was a brief moment in one of the arias where the orchestra pulled back. Just harp and cello. A duet.

I can still hear it.

The harpist was a visiting musician from Europe — I can't recall her name now, but I remember her elegance, the shimmering precision of her playing. And then there was Nasran.

His cello didn't just play the notes. It sang.

There's a difference, you see, between technically proficient cellists and those who can make the instrument breathe. String tone especially on cello, requires more than practice. It demands years of refinement, an understanding of color, depth, intensity. To play dolce, to shape a phrase with tenderness even while maintaining power, is a rare skill.

Nasran had it.

Even the guest conductor, I believe he was German — looked visibly moved. You could see it in his face, the slight pause before he smiled, that universal recognition among musicians when someone has just done something beautiful.

I felt proud in that moment. Proud that this sound — this world-class, internationally competitive sound was coming from a Malaysian musician. From someone I knew. From Nasran.

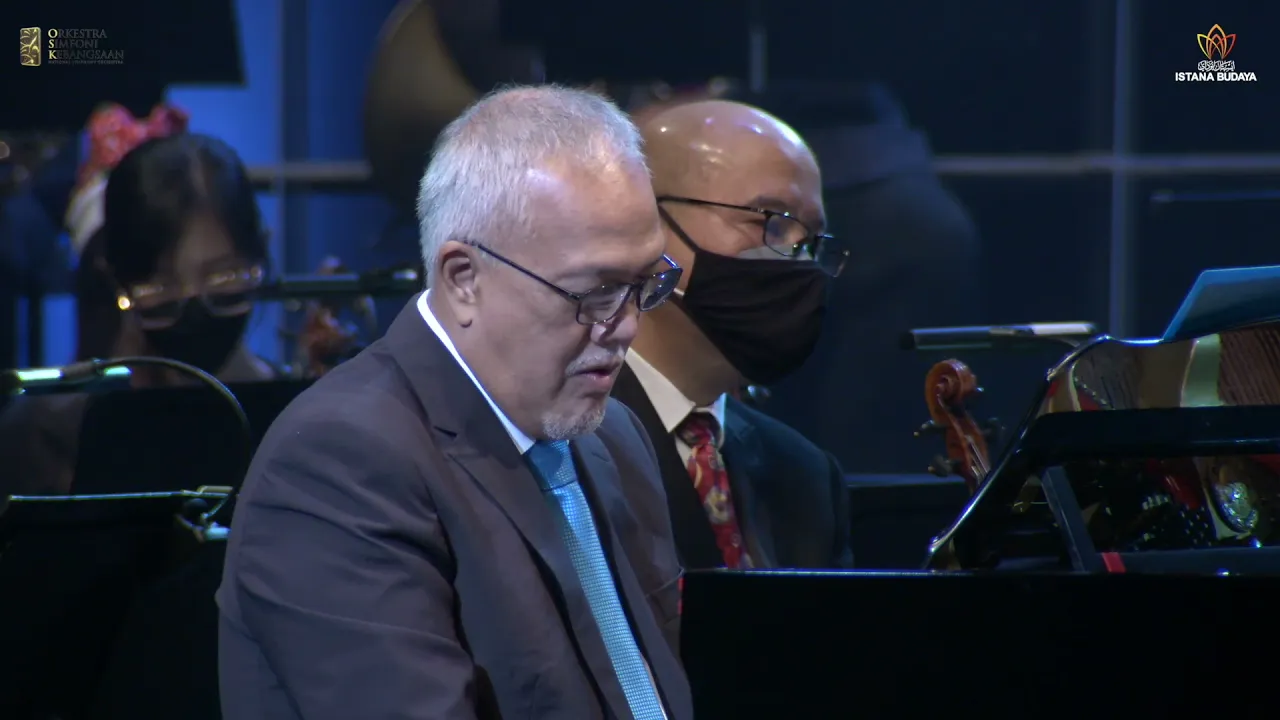

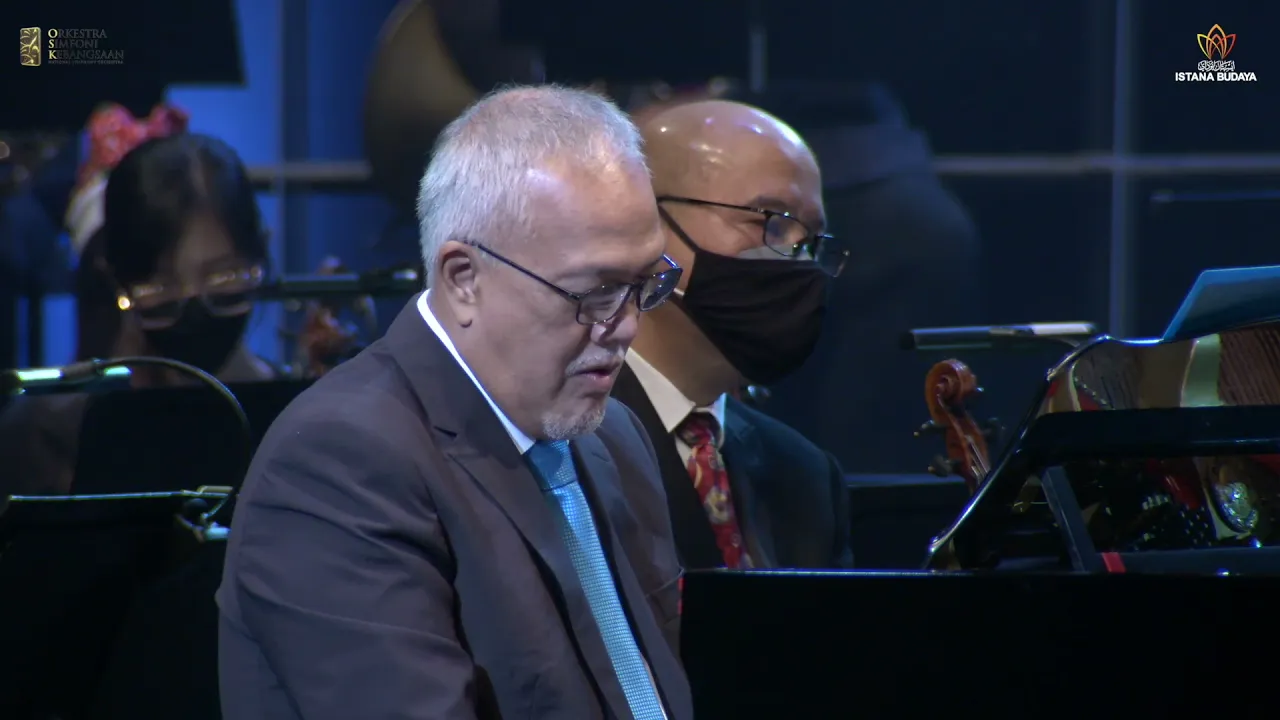

The Lambang Sari Series: Resilience and Triumph National Symphony Orchestra conducted by Nasran Nawi, featuring internationally acclaimed pianist Muzaffar Abdullah. The program showcases masterworks by Berlioz, Ravel, and Sibelius—a celebration of Western classical repertoire performed by Malaysia's finest musicians.

The Man Behind the Baton

Fast forward to today. Nasran Nawi is no longer just the Principal Cellist. He's the Music Director of the National Symphony Orchestra, leading an institution he helped build from its earliest days. He's one of the pioneers—part of the generation that gave Malaysia a world-class orchestra when we barely had the infrastructure to sustain one.

But leadership, he tells me now, is a different kind of weight.

"During the five years of leading this orchestra," he begins, his voice calm but carrying the fatigue of experience, "what people don't see is the human part. I know every single one of the seventy musicians we have. Forty of them are full-time. And what's tough isn't the music — it's never the music. Music stress is fine. I enjoy it, even when it's challenging."

He pauses.

"But the human part? That's where it gets hard. Dealing with people. With personal situations. Most of these musicians are my friends. That makes it harder, because when you have to make decisions, merely tough decisions — you're not just managing an orchestra. You're managing relationships. Friendships. I know their families. I know their struggles. And balancing all of that while still maintaining artistic standards? That's the challenge nobody talks about."

It's a rare admission. Orchestra management is often romanticized from the outside — the maestro on the podium, commanding music into being. But Nasran's honesty cuts through that. Leadership in the arts isn't just about musicality. It's about navigating human fragility while trying to create something extraordinary.

"I don't want to manage people anymore," he says, almost quietly. "I still love music. I still love the music part, even when it's demanding. But dealing with people for five years straight? That's enough. I'd rather just focus on the friend part, on the human connection, without the weight of also having to discipline them or make hard calls about their futures."

When he's not at the orchestra, Nasran finds his escape on the golf course. Every weekend, you'll find him at one of Kuala Lumpur's courses, trading the precision of musical timing for the precision of a golf swing. It's a different kind of discipline, one that asks nothing of him except his own focus.

Nasran Nawi conducting National Symphony Orchestra in Concert of Polar Express Concert Suite at Istana Budaya ,The National Theatre.

Fine Arts Treated as Luxury rather than Necessities

When I ask what keeps him going despite this exhaustion, his answer is immediate.

"Education."

He leans forward slightly, the way people do when they're about to say something they believe deeply.

"I would like to see more focus on education. It's the only way to build an audience. Right now, people— most people — don't know quality. They can't distinguish between a good musician and a great one. And I don't mean that to sound elitist. I mean it practically. Without education, we can't grow. Not just in classical music, but in any kind of music. Jazz, traditional, contemporary, it doesn't matter. If people don't understand what they're listening to, they can't appreciate it. And if they can't appreciate it, they won't support it."

He's not wrong. Malaysia's arts scene has long struggled with this tension — the question of how to build audiences when cultural education isn't prioritized in schools, when fine arts are treated as luxuries rather than necessities.

"Music education isn't about forcing people to like classical music," Nasran continues. "It's about teaching them to listen. To recognize craftsmanship. To understand why one performance moves you and another doesn't. Right now, the challenge isn't just performance quality—it's that we're performing for people who haven't been given the tools to fully engage with what we're doing."

It's a systemic issue, one that can't be solved by individual orchestras alone. But Nasran believes it's essential. "If we want to build real audiences — the kind that will sustain orchestras and musicians for decades — we have to start with education. That's where everything begins."

National Symphony Orchestra featuring Michael Veerapan, famous well-known legendary Jazz Pianist in Jazz Music Scene in Malaysia, conducted by Nasran Nawi

What He Said in Younger Musician

I ask him what advice he'd give to the young cellist who first joined the NSO decades ago, before he knew what leadership would demand of him.

He smiles faintly.

"I'd tell myself that the music is the easy part. The artistry, the technique, the performances—those you can master if you're willing to work. But the people? The relationships? That's where the real test is. And you can't prepare for it in a practice room."

There's a heaviness to that truth, but also acceptance. Nasran isn't bitter. He's realistic. He understands that building something as ambitious as Malaysia's National Symphony Orchestra required more than talented musicians. It required people willing to carry weight—artistic, administrative, emotional.

And for soon to be five years as Music Director, he's carried it.

A rare collaboration between Malaysian pop and classical music, featuring vocalist Ernie Zakri with the National Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Nasran Nawi. Performed at Konsert Patriotik Tanah Airku in conjunction with Malaysia's Independence Day celebrations

A Legacy in Sound

Before I leave, I ask him one more question: "What do you want people to remember about your time with the NSO?"

He doesn't hesitate.

"I want them to remember that we tried. That this generation of musicians—the pioneers—gave everything we had to build something lasting. Not perfect, but real. And I hope the next generation understands what it took to get here, so they can build on it rather than start over."

It's a modest answer from someone who's been part of one of Malaysia's most significant cultural achievements. But that's Nasran — never loud, never demanding the spotlight, just consistently excellent, consistently present.

The boy from Ipoh, who earned a scholarship to study cello in Germany. The principal cellist whose sound could silence a room. The Music Director who led with humanity even when it cost him peace.

Between the silence and the symphony, Nasran Nawi has spent a lifetime creating space for both.

And that, perhaps, is legacy enough.

The National Symphony Orchestra performs regularly at Istana Budaya, The National Theatre, Jalan Tun Razak.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. Upcoming NSO concert in 2026 features collaborations with famous pop artist — a rare crossover between classical and contemporary Malaysian music. For details and reservations, contact Istana Budaya.

22Muse Media is a Southeast Asian luxury lifestyle publication covering culture, business, and the people shaping the region's creative landscape. For profile featuring and brand partnership, do contact editor@22musemedia.com

A conversation with Nasran Nawi, Music Director, Malaysia National Symphony Orchestra

Words by Adinazeti Adnan

Photos : National Symphony Orchestra

The First Encounter

The first time I saw Nasran Nawi, I was nineteen years old.

An intern violinist with the National Symphony Orchestra, barely holding my own among seasoned professionals, I was overwhelmed by everything — the grandeur of Istana Budaya, the precision demanded in every rehearsal, the unspoken hierarchy that exists in any orchestra. And then this man approached me.

Not with the stern authority I'd come to expect from principals, but with warmth. Nasran Nawi was the Principal Cellist then, in the year 2000, and he simply wanted to know my name. To break the ice. To see how I was settling in.

I remember thinking he had the presence of a father figure — the kind of musician who saw young students not as burdens to tolerate, but as futures to nurture.

Then he looked at my violin.

Within seconds, his expression changed. Urgency replaced ease. "Wait — your strings," he said, reaching for my instrument before I could process what was wrong. I'd strung my violin incorrectly. The D and A strings were reversed, a beginner's mistake that could have gotten me scolded during rehearsal, especially under Datuk Mustafa Fuzer Nawi's baton, our conductor at the time. Mustafa was known for his exacting standards, his low tolerance for carelessness.

But Nasran didn't scold. He fixed it.

In less than two minutes, he restrung my violin, tuned it with practiced speed, and handed it back. "Cepat, cepat tukar. Nanti kena marah." Hurry, change it now before you get reprimanded.

He saved me that day. Not just from embarrassment, but from the kind of mistake that marks you early in a professional setting. I've never forgotten that moment — or the kindness behind it.

Nasran Nawi conducting National Symphony Orchestra at Petronas Philharmonic Hall

The Sound That Stayed

There was another memory, quieter but just as profound.

It happened during an opera production — Puccini's Tosca, performed by Istana Budaya sometime around 2001 or 2002. The NSO was in the pit, accompanying the singers, and there was a brief moment in one of the arias where the orchestra pulled back. Just harp and cello. A duet.

I can still hear it.

The harpist was a visiting musician from Europe — I can't recall her name now, but I remember her elegance, the shimmering precision of her playing. And then there was Nasran.

His cello didn't just play the notes. It sang.

There's a difference, you see, between technically proficient cellists and those who can make the instrument breathe. String tone especially on cello, requires more than practice. It demands years of refinement, an understanding of color, depth, intensity. To play dolce, to shape a phrase with tenderness even while maintaining power, is a rare skill.

Nasran had it.

Even the guest conductor, I believe he was German — looked visibly moved. You could see it in his face, the slight pause before he smiled, that universal recognition among musicians when someone has just done something beautiful.

I felt proud in that moment. Proud that this sound — this world-class, internationally competitive sound was coming from a Malaysian musician. From someone I knew. From Nasran.

The Lambang Sari Series: Resilience and Triumph National Symphony Orchestra conducted by Nasran Nawi, featuring internationally acclaimed pianist Muzaffar Abdullah. The program showcases masterworks by Berlioz, Ravel, and Sibelius—a celebration of Western classical repertoire performed by Malaysia's finest musicians.

The Man Behind the Baton

Fast forward to today. Nasran Nawi is no longer just the Principal Cellist. He's the Music Director of the National Symphony Orchestra, leading an institution he helped build from its earliest days. He's one of the pioneers—part of the generation that gave Malaysia a world-class orchestra when we barely had the infrastructure to sustain one.

But leadership, he tells me now, is a different kind of weight.

"During the five years of leading this orchestra," he begins, his voice calm but carrying the fatigue of experience, "what people don't see is the human part. I know every single one of the seventy musicians we have. Forty of them are full-time. And what's tough isn't the music — it's never the music. Music stress is fine. I enjoy it, even when it's challenging."

He pauses.

"But the human part? That's where it gets hard. Dealing with people. With personal situations. Most of these musicians are my friends. That makes it harder, because when you have to make decisions, merely tough decisions — you're not just managing an orchestra. You're managing relationships. Friendships. I know their families. I know their struggles. And balancing all of that while still maintaining artistic standards? That's the challenge nobody talks about."

It's a rare admission. Orchestra management is often romanticized from the outside — the maestro on the podium, commanding music into being. But Nasran's honesty cuts through that. Leadership in the arts isn't just about musicality. It's about navigating human fragility while trying to create something extraordinary.

"I don't want to manage people anymore," he says, almost quietly. "I still love music. I still love the music part, even when it's demanding. But dealing with people for five years straight? That's enough. I'd rather just focus on the friend part, on the human connection, without the weight of also having to discipline them or make hard calls about their futures."

When he's not at the orchestra, Nasran finds his escape on the golf course. Every weekend, you'll find him at one of Kuala Lumpur's courses, trading the precision of musical timing for the precision of a golf swing. It's a different kind of discipline, one that asks nothing of him except his own focus.

Nasran Nawi conducting National Symphony Orchestra in Concert of Polar Express Concert Suite at Istana Budaya ,The National Theatre.

Fine Arts Treated as Luxury rather than Necessities

When I ask what keeps him going despite this exhaustion, his answer is immediate.

"Education."

He leans forward slightly, the way people do when they're about to say something they believe deeply.

"I would like to see more focus on education. It's the only way to build an audience. Right now, people— most people — don't know quality. They can't distinguish between a good musician and a great one. And I don't mean that to sound elitist. I mean it practically. Without education, we can't grow. Not just in classical music, but in any kind of music. Jazz, traditional, contemporary, it doesn't matter. If people don't understand what they're listening to, they can't appreciate it. And if they can't appreciate it, they won't support it."

He's not wrong. Malaysia's arts scene has long struggled with this tension — the question of how to build audiences when cultural education isn't prioritized in schools, when fine arts are treated as luxuries rather than necessities.

"Music education isn't about forcing people to like classical music," Nasran continues. "It's about teaching them to listen. To recognize craftsmanship. To understand why one performance moves you and another doesn't. Right now, the challenge isn't just performance quality—it's that we're performing for people who haven't been given the tools to fully engage with what we're doing."

It's a systemic issue, one that can't be solved by individual orchestras alone. But Nasran believes it's essential. "If we want to build real audiences — the kind that will sustain orchestras and musicians for decades — we have to start with education. That's where everything begins."

National Symphony Orchestra featuring Michael Veerapan, famous well-known legendary Jazz Pianist in Jazz Music Scene in Malaysia, conducted by Nasran Nawi

What He Said in Younger Musician

I ask him what advice he'd give to the young cellist who first joined the NSO decades ago, before he knew what leadership would demand of him.

He smiles faintly.

"I'd tell myself that the music is the easy part. The artistry, the technique, the performances—those you can master if you're willing to work. But the people? The relationships? That's where the real test is. And you can't prepare for it in a practice room."

There's a heaviness to that truth, but also acceptance. Nasran isn't bitter. He's realistic. He understands that building something as ambitious as Malaysia's National Symphony Orchestra required more than talented musicians. It required people willing to carry weight—artistic, administrative, emotional.

And for soon to be five years as Music Director, he's carried it.

A rare collaboration between Malaysian pop and classical music, featuring vocalist Ernie Zakri with the National Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Nasran Nawi. Performed at Konsert Patriotik Tanah Airku in conjunction with Malaysia's Independence Day celebrations

A Legacy in Sound

Before I leave, I ask him one more question: "What do you want people to remember about your time with the NSO?"

He doesn't hesitate.

"I want them to remember that we tried. That this generation of musicians—the pioneers—gave everything we had to build something lasting. Not perfect, but real. And I hope the next generation understands what it took to get here, so they can build on it rather than start over."

It's a modest answer from someone who's been part of one of Malaysia's most significant cultural achievements. But that's Nasran — never loud, never demanding the spotlight, just consistently excellent, consistently present.

The boy from Ipoh, who earned a scholarship to study cello in Germany. The principal cellist whose sound could silence a room. The Music Director who led with humanity even when it cost him peace.

Between the silence and the symphony, Nasran Nawi has spent a lifetime creating space for both.

And that, perhaps, is legacy enough.

The National Symphony Orchestra performs regularly at Istana Budaya, The National Theatre, Jalan Tun Razak.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. Upcoming NSO concert in 2026 features collaborations with famous pop artist — a rare crossover between classical and contemporary Malaysian music. For details and reservations, contact Istana Budaya.

22Muse Media is a Southeast Asian luxury lifestyle publication covering culture, business, and the people shaping the region's creative landscape. For profile featuring and brand partnership, do contact editor@22musemedia.com

Share

Copy link

Share

Copy link

Related

Orchestra • Luxury Hotels • Fine Dining • Business Leaders • Cultural Icons

●

STORIES THAT STAY

●

2025

●

Singapore • Bali • Dubai

•

© 22Muse Media

2025

Subscribe for BUSINESS + CULTURE insights

Orchestra • Luxury Hotels • Fine Dining • Business Leaders • Cultural Icons

●

STORIES THAT STAY

●

2025

●

Singapore • Bali • Dubai

•

© 22Muse Media

2025

Subscribe for BUSINESS + CULTURE insights